“I Dreamed of the Perfect Image on My Phone Every Night.” How Online Trends Are Pushing Girls into Eating Disorders

By Borislava Popova

A consciousness capable of suppressing a primal human instinct. A successful lady who has long since achieved the ideal of beauty. And a 12-year-old girl who is crossing the threshold of her own femininity.

What do the three have in common? It lies somewhere between the small screen and the vast space called the “social network”. An ideal world in which you are welcome only if you are perfect. If not you, then at least your body.

“When I get hungry, it is not time to eat. I always drink water.”

This is one of the many pieces of advice from the so-called “fitness influencers” that 15-year-old Alexandra* follows on social networks. Every day she wakes up with the dream of a certain number on the scale and makes the decision to starve until she achieves it. And to do so, she is ready to go “all the way”, without setting any limits for herself.

“It was my outlet. I felt that there were people like me who understood me,” Alexandra tells sCOOL Media.

Today, she is 16 and that period of her life is behind her. However, the scars of the long months in which she lived with the idea of the perfect body from TikTok and Instagram remain – to the point where she neglected her health and even went as far as anorexia.

Such online content creates in Alexandra and thousands of other girls like her a feeling of pressure and longing for unattainable perfection, which is expressed in an unhealthy thin body. Sometimes this perfection is achievable, even realistic. But at the cost of your own health.

#SkinnyTok or hunger as a way of life

According to the statistical portal Datareportal, Bulgaria ranks sixth in the world in terms of time spent on TikTok for 2024, overtaking even the USA. 97% of young people in the world between the ages of 13 and 18 are active users of the platform.

The results are much more than statistics. They illustrate the daily lives of thousands of teenage girls who are still forming their own self-esteem. Behind the percentages lie destinies beyond the digital space.

For 16-year-old Kalina*, it all started when she was just 12 and spent entire days on social networks. Before long, she came across videos like “What I Eat in a Day” and “Beach Shape in Just 20 Days” with thousands of views and comments.

The videos are diverse and gain popularity in minutes. They are united by a short name: #SkinnyTok – a community in which young girls daily share videos with diet plans, tips for “fast weight loss” and a “perfect body”.

According to Proletina Ilcheva, an expert from the Safer Internet Center, “the lack of transparency in the videos gradually instills in girls dissatisfaction with their lifestyle”.

“Little by little, with each subsequent video, I began to believe that I was not enough and that I had to change in order to fit into the ideal,” Kalina says.

Gradually, she became convinced that the femininity she dreamed of was only possible if her body was very thin. In her mind, weight was no longer just a number, but an indicator of her own worth. For the 12-year-old girl, hunger was also an attempt to belong:

“I was looking for approval, recognition, human value in my appearance,” says Kalina.

“I felt that there were people like me who understood me,” says Alexandra. For her, the phone is a “comfort” and a refuge from loneliness.

But what is this virtual refuge?

Globally, #SkinnyTok is gradually becoming a phenomenon. On TikTok, hashtags like #WhatIEatInADay and #BeachBody have over 15 billion views.

Although in our country this trend is perceived as a distant phenomenon, the reality is different.

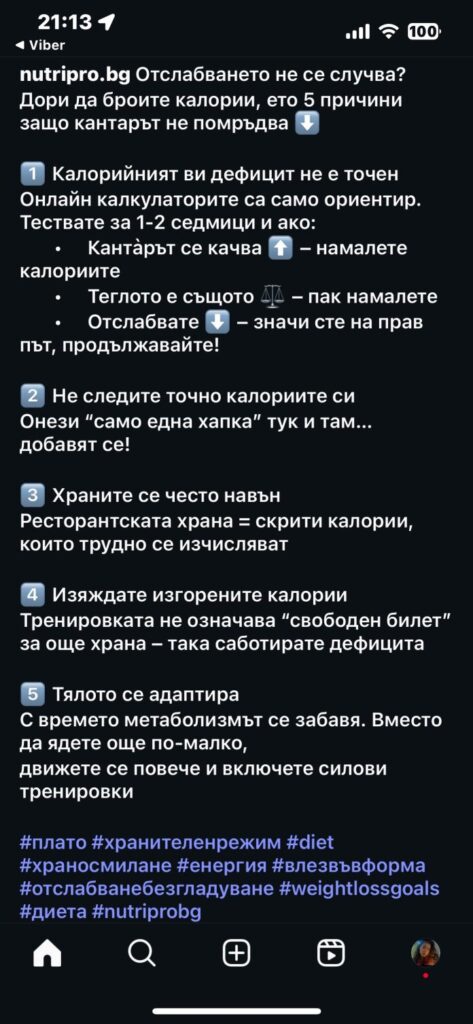

Entering TikTok, a Bulgarian user witnesses a series of videos created in an easily accessible language, not only by foreign, but also by Bulgarian influencers. For example, one of the publications advises us to systematically reduce our calorie intake until we start losing weight.

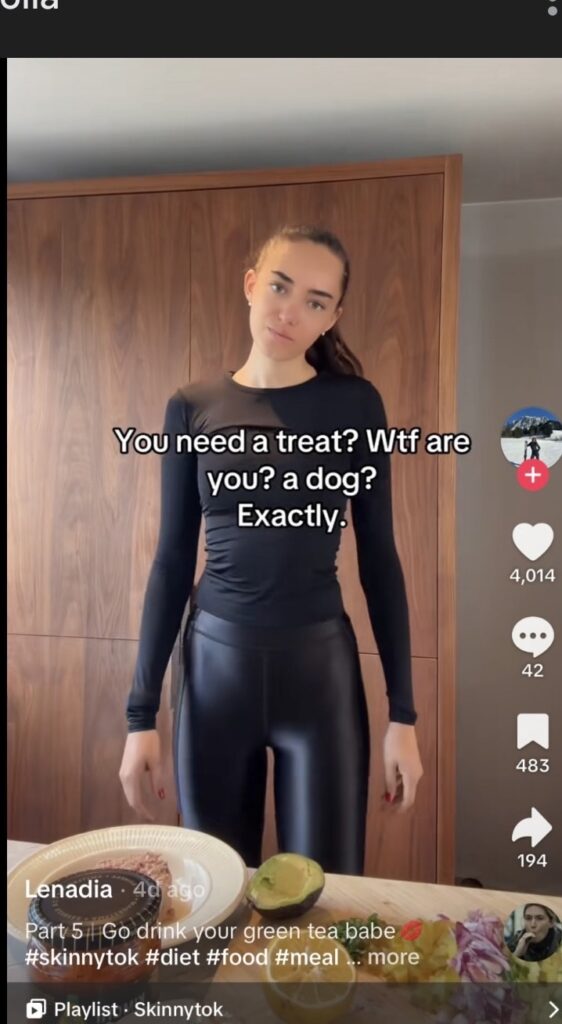

In foreign publications, we see messages like “Do you need a treat? What are you – a dog?” and “What you eat in private will be revealed in public.”

“The videos worked as motivation to continue with the deprivation. They helped me normalize hunger,” says Kalina.

“Social networks instill the distorted idea that being thin leads to a higher social status,” Proletina Ilcheva also shares.

Proof of this is the fact that the comments on such videos are mostly compliments to their creators.

“I read comments every day. Everyone wrote: You have a beautiful body, how did you achieve it? I thought: Yes, so I’m doing the right thing,” recalls Alexandra.

She calls watching such videos a “spiral.” Experts who have studied the Bulgarian online space also come to the same conclusion. Even in the case of a conscious choice, ignoring such type of content is difficult.

“The very structure of social networks supports the rapid spread of such unrealistic ideas through personalization algorithms. They can increase the display of content related to extreme diets or distorted body image, especially after initial interaction with such videos. If you watch even one video that has “dieting” content, you are soon flooded with an avalanche of similar videos,” Stella Bileva, a clinical psychologist at the Animus Association, tells sCOOL Media.

The danger often remains hidden

But if we ask a teenage girl, the danger simply does not exist.

“This lifestyle is presented in such an unrealistic way that it is impossible to realize that it is unhealthy. The word hunger does not exist, they call it discipline, self-improvement,” Kalina points out.

This belief makes the problem even more difficult to grasp. The line between a healthy lifestyle and an eating disorder is completely blurred, and hunger is disguised as “will” and “self-actualization.”

As she sees her favorite jeans becoming baggy, Alexandra doesn’t feel ashamed, she doesn’t think she needs help. Quite the opposite:

“I felt terribly alone, but I believed that since I was able to suppress a basic human instinct, I was better than everyone else. It was social media that influenced me in this direction,” she says.

The main appeal, made daily by psychologists, doctors, and specialists, consists of two words: “Seek help.”

However, help is possible when both parties recognize its necessity. When you fall under the umbrella of “stigma,” it is not easy to seek support.

“Those going through an eating disorder are stigmatized,” say the Safer Internet Center.

According to an American study from 2024, 64% of people with increased symptoms of eating disorders refuse to seek help. The reason – fear of disapproval and feelings of guilt. The trend in Bulgaria is identical.

“In Bulgarian society, concepts like depression, anxiety and eating disorders have become taboo topics,” says Kalina.

“I knew there were girls who starved themselves, but I couldn’t imagine that it could happen to me. In Bulgaria, it is considered that if you do it, you are strange,” adds Alexandra.

When it comes to sharing with loved ones, one thing is clear: no one asked them.

The way back

“I am not the same person after all. Something in me died.”

With these words, Alexandra begins a different story. A year later, she looks the same as before, but in reality, nothing is the same. She shares that the battle to find yourself again lasts “forever” and requires you to realize that hunger does not come alone, but is also connected to other problems.

“Eating disorders are a symptom of a deeper internal conflict and often reflect strong psycho-emotional distress,” confirms psychologist Stella Bileva.

“Usually, they are caused by a combination of low self-esteem, a sense of lack of control and past trauma. They are usually combined with other mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, which reinforce each other and make the picture worse,” Bileva adds.

According to her, for many people, an eating disorder becomes a way to exercise control when they feel powerless. But while in Alexandra’s mind her condition is incurable, the therapist is categorical: there is always salvation.

“It is important for girls to know that there is a way out – an eating disorder is not a sentence, but a condition that can be overcome,” says Bileva.

However, there is no universal solution: “Although the problem may seem the same, the reasons for each person are different. That is why the words that those going through an eating disorder need are not universal,” she explains, advising to avoid condemnation and body comments such as “you look like a skeleton.” Rather, a dialogue should be opened with a calm intonation and words like: “I notice that you are more worried. What is happening, tell me,” says the psychologist.

In Bileva’s words, an eating disorder is “a disease of the entire family environment” and the behavior of the parents has a key influence.

“In the family, change starts with the language and atmosphere at home. It is important for parents to avoid stigmatizing comments about the body. The family is also the first place where worrying signs can be noticed, and then it is important to seek professional help in a timely manner,” she emphasizes.

But despite its individuality, the path back for each girl requires something in common: professional help.

“The sooner a psychologist and psychiatrist get involved, the greater the chance of recovery,” says Bileva.

In a world that has elevated perfection to a pedestal, two girls risk their health to find it. They manage to get closer to it with videos, photos, and advice that promise instant results. But they lose themselves along the way.

“I don’t wish this on anyone. You don’t just lose weight, you lose yourself,” says Alexandra.

Today, she and Kalina are 16 years old. Having lost themselves once, they choose to rebuild themselves.

Funded by the OPEN SPACE Foundation (OSF) project “Youth against disinformation”, implemented in partnership with the Association of European Journalists in Bulgaria (AEJ-Bulgaria), with the support of the British Council in Bulgaria. However, the views and opinions expressed are entirely those of their author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of OSF, AEJ and the British Council in Bulgaria. Neither OSF, AEJ nor the British Council in Bulgaria are responsible for them.